Which Things Are Valuable?

If You Want To Know What To Value, You Need To Understand What Makes Things Valuable

One of the main aims of a micro-philosophy is to help people structure their lives around a system of values.

Last week, I explained how to identify your 10 core values that constitute your practical self.

In this week's newsletter, I want to help you understand how to think more clearly about values in relation to action.

Understanding how values and actions are connected will allow you to tap into the value of value.

It will make it possible for you to begin living a principled and authentic life where your decisions come from a place of depth.

Imagine what it feels like to become the world's leading expert on your own system for living.

Imagine understanding how every important decision you make fits into your grand vision.

That is the long term goal of the micro-philosophy.

But how do we take the things we value and act on them?

Before I explain that, it is important to explain what makes things valuable and why we choose to fight for some things, and completely avoid others.

The 4 Ways That Something Can Be Valuable

It is commonly accepted that there are 4 ways in which something can be valuable or good (I am using them to mean the same thing here).

These categories are not meant to be the end all be all, but provide some incredibly powerful conceptual tools to help you think more deeply about how your actions relate to your deeply held values.

Let's dig in.

1) Instrumental Value

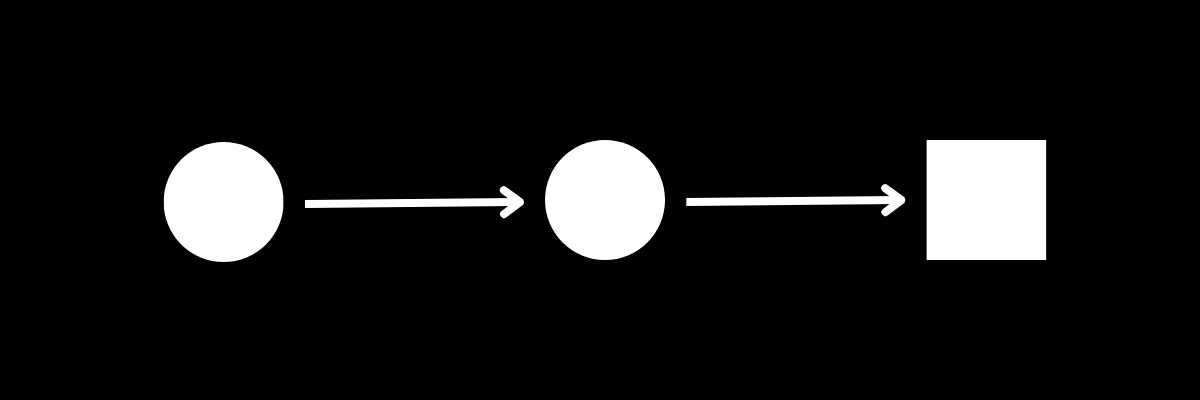

The first way that something can be valuable is by allowing you to get something else that is valuable.

This is called instrumental value.

The most intuitive example is money.

Almost everyone would agree, except maybe someone who collects old coins as a hobby, that money is only valuable because of what it helps us get.

In order to see this, imagine that you were on a desert island by yourself, and completely cut off from the world, but you had 10 Billion dollars.

Since there is no way to use the money to get anything on the desert island, it loses all of its value.

You might use it to start a fire at this point, but in this case it isn't the money that is valuable, it is the material that it is made out of — the paper.

2) Final Value

The opposite of instrumental value has been called final value.

While something like money has instrumental value because it is a means to getting something else, something like happiness is often thought to exemplify final value, because it is the final goal at which we aim.

The value of happiness is final in the sense that the last stop on a train is final.

It is the end destination of our choices.

In the famous opening chapter of his treatise on ethics, Aristotle argued that the final goal at which human beings aim in their life is happiness.

Aristotle also concluded that, since happiness is the final goal, it is also therefore the highest good, or the most good thing that we can pursue.

The basic connection here is that a goal is, in some sense, good to achieve.

Aristotle thought that the highest good must be happiness because happiness is desired or chosen "for its own sake", and never for the sake of something else.

Aristotle writes:

"[F]or this we choose always for itself and never for the sake of something else, but honor, pleasure, reason, and every virtue we choose indeed for themselves (for if nothing resulted from them we should still choose each of them), but we choose them also for the sake of happiness, judging that by means of them we shall be happy. Happiness, on the other hand, no one chooses for the sake of these, nor, in general, for anything other than itself" (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book One)

So, happiness represents something that has final value.

As Aristotle makes clear, happiness is not the only thing that has final value, but it is the most final of them all.

3) Extrinsic

The first two ways in which something can be valuable concerned how we choose or use things.

In other words, they help clarify what makes something valuable from the perspective of choosing what to do and taking action.

The next two ways of thinking about what makes something valuable concern the objects of value themselves.

Another way that philosophers talk about this is the source of value, or the nature of value.

Where does the value of something come from?

Let's go back to the money example to help us answer this question.

Most people would agree that the value of money does not come from the money itself, but from an external source, such as the economic system, the market, or other people.

This is why if there was no economic system or people around, money would lose its value.

It would be cut off from the source of its value.

In cases such as this, the value of something like money is said to be extrinsic or external to the object that has value.

The value of money comes entirely from what people think about it, the economic system, and how people are able to use it to get what they want.

4) Intrinsic

The fourth and final way in which something can be valuable is when the value of an object or person comes from within the object itself.

If extrinsic value is external and depends on something outside of the thing itself, then intrinsic value is internal and does not depend on anything outside of the object itself.

For example, you might think that the value of a work of art is intrinsic because it is valuable whether or not anyone is aware of it, or cares about it.

Alternatively, you might think that things like knowledge or health have intrinsic value because all or some of their value is internal, and does not depend on whether or not they are useful for anything.

It is worth noting that not everyone believes intrinsic value is a real thing.

Some people think that nothing in the world is valuable by itself, and the value of everything comes from human beings seeing or thinking that something is valuable.

While this is a popular idea, it also conflicts with many commonly held beliefs, such as the belief that human life has some intrinsic value.

If human life did not have intrinsic value, then it would be difficult to make sense of things like human rights, funeral rights, and justice.

Not impossible, but difficult.

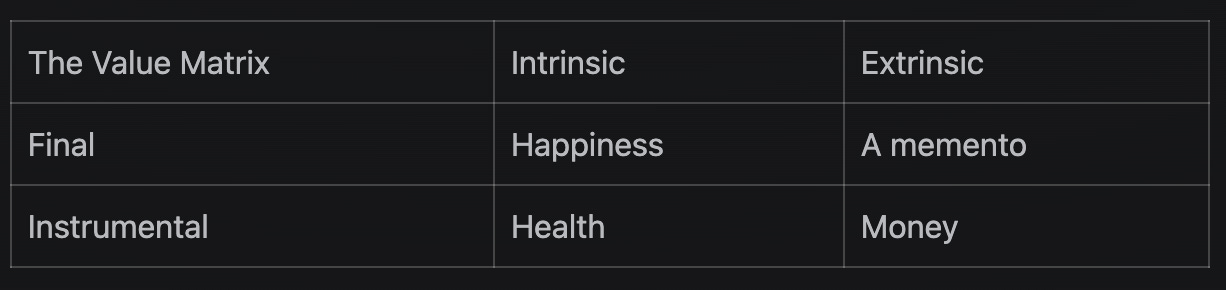

The Value Matrix: Combining The 4 Types Of Value

At this point you may be wondering how these different kinds of value are related or whether they can overlap in various ways.

Most philosophers would agree that people or things can be valuable in multiple ways, combining these four types of value together (while also respecting the distinction between intrinsic/extrinsic and final/instrumental).

It is possible to represent the possible combinations in the following way:

Let's go through each of the 4 possible combinations in the table and clarify what kinds of examples fall into each category.

Combination #1: Intrinsic and Final

To say that something or someone has both intrinsic and final value is to say that they are valuable because of the sort of thing that they are and that they are valuable for no further reason or purpose.

This category often is understood to capture our highest ideals and virtues, such as:

Happiness

Justice

Friendship

Courage

Duty

It can also be used to help make sense of the sorts of activities and hobbies that people dedicate significant time and attention to such as:

Painting

Dancing

Music

Games

Socializing

It is plausible to say that human beings pursue these sort of activities both because of the features of the activities themselves that are appealing, and for no further or higher purpose.

One caveat to this is that, for a philosopher like Aristotle, these activities are able to be chosen for their own sake, but also because they make us happy. For Aristotle, happiness is the ultimate end or final value of everything that we do. Not every philosopher would agree with Aristotle about this, but he was famous for being the first philosopher to develop and defend the idea.

So, according to Aristotle, an artist might choose to paint for its own sake, but also because it is what makes them happy.

The combination of intrinsic and final value is useful for thinking about the sorts of pursuits that give our lives meaning and purpose.

Combination #2: Intrinsic and Instrumental

A classic example of something that is both intrinsically valuable and instrumentally valuable is knowledge.

Most people would agree that the value of knowledge doesn't depend on anything, and that knowledge for knowledge's sake is, at least to some extent, valuable.

This does not mean that it can't be used for helping us improve the world, or improve our lives.

To say that knowledge has intrinsic value is not to require that it has no other kind of value, it is just to ascribe to knowledge at least some value that it had independently of anything else.

That being said, knowledge clearly is instrumentally valuable as well.

Knowledge helps us solve problems, build things, and improve our lives both individually and collectively.

Combination #3: Extrinsic and Final

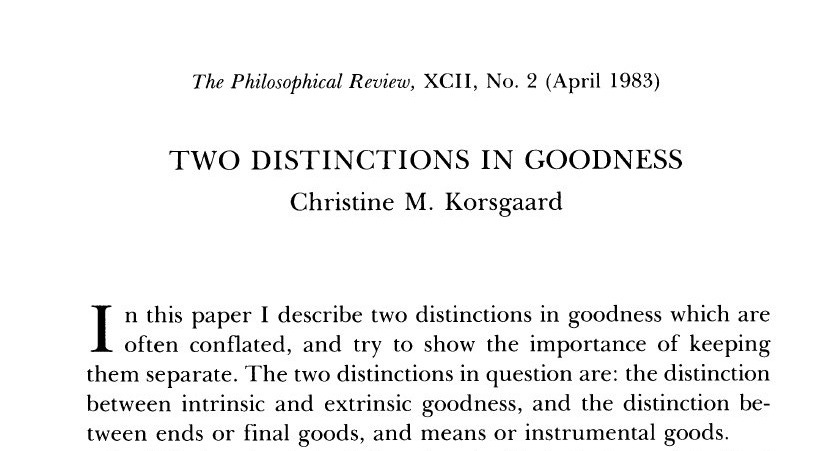

This category is interesting because many philosophers did not recognize it as a conceptual possibility in the history of philosophy.

Intrinsic value and final value have often been treated to be the same thing throughout the history of philosophy, but in the late 20th century, the American philosopher Christine Korsgaard argued that they are actually distinct.

Korsgaard argued that it is possible for things to be valuable non-instrumentally even though the source of value is extrinsic.

To say that something has extrinsic value is to say that the source of its value is external to the object itself. That much isn't very hard to grasp. We assign or project value onto inanimate objects all of the time.

For example, imagine your grandfather gave you a plastic game piece that by itself seems to have no real value. It isn't beautiful, it isn't made out of rare materials, and so on. But, it really meant a lot to you because of the memories of your grandfather.

The source of the value of this plastic game piece for you is the context and memories that made it have value, not the piece itself.

To say that it has final value is that you value the piece for no other purpose beyond the fact that your grandfather gave it to you. As a result, you may never want to sell it, or trade it, for anything. It's value to you is final and serves no further purpose.

Combination #4: Extrinsic and Instrumental

The fourth category is the most intuitive and one that is sometimes, mistakenly, taken to represent the only real kind of value.

To say that something is extrinsically and instrumentally valuable is to say that its value comes from some external facts, like the game piece, and it is valuable not for its own sake, but because of how it can be used to get something else.

The most obvious example here is money, but you could also put many things into this category as well, such as tools, and even fame.

There is a strong temptation, especially in capitalist societies, to reduce all forms of value to extrinsic and instrumental value. This is unfortunate because it has seriously harmful effects on things such as education, the humanities, and human flourishing.

It also makes the world much more boring.

This does raise an important question which you may have been wondering about while reading this:

Who gets to decide what does and does not have value?

Value Realism vs. Value Anti-Realism

The debate between Value Realism and Anti-Realism is one of the most fascinating debates in the history of philosophy because it touches on deep questions that threaten to undermine the assumptions by which we live.

To see why, imagine that you are someone who has decided to dedicate their life to art. You deeply believe that some artworks are valuable, so you spend thousands of hours studying them and learning how to appreciate them. You spend money buying art, and traveling to visit art museums. You argue with people about why some artworks are better than others. In short, you dedicate your life to art.

Now imagine that one day, you read some philosophy, and become convinced that all value statements are meaningless, and that there is no such thing as values in the world. In short, values are not real.

This would, no doubt, be a painful revelation.

It would mean that you wasted your entire life studying something that is total nonsense.

That would be a tragic outcome for someone's life.

This is all to say that what we believe and how we live are deeply connected.

No one wants to live their entire life on the basis of something that isn't true.

Truth has value.

But what does that really mean?

What does it mean to say that truth, or justice, or beauty, or a painting have value?

That is the question debated by realists and anti-realists.

Value Realism is the philosophical position that there are objective facts about what has value, independently of what subjects believe or prefer. Additionally, value realists often believe that value judgments, such as the claim that "The Mona Lisa is beautiful" or "The Grand Canyon is majestic" can be true or false statements about what the world is actually like.

Value Anti-Realism is the position that there are no objective facts about value, and that value judgments are neither true nor false. How can you say anything true about values if there are no values? Likewise, most people would agree that we can't really say anything true about dragons, since they don't exist. For someone who believes in Value Anti-Realism, saying that "The Mona Lisa is beautiful" is like saying that "Dragons are beautiful".

So, who gets to decided what has value and what doesn't?

The only real answer to that question is that you have to decide whether you believe that there are things which have objective value, whether nothing truly has value, or whether the truth is more complicated than that.

In building a micro-philosophy, it is essential to try and articulate your core beliefs about this question because values determine and shape our actions and, more importantly, our entire lives.

Weekly Assignment

In this week's assignment, I want you to use these new concepts to think more deeply about the sorts of things you take to be valuable and why.

This will help you take a step in the direction of turning your values into action.

In next week's newsletter, I will discuss how to bridge that gap completely.

Before that, it is important to first think about why we choose what we choose, and what makes the things we value valuable.

This will make it easier to construct principles in the future that allow you to act in ways that align with your values.

This week's assignment is very straightforward.

Think Of 10 Examples For Each Category Of Value

For each of the 4 categories of value (Final, Instrumental, Intrinsic, Extrinsic), come up with 10 examples of things that you believe serve as clear examples of each:

What are 10 things that you think are instrumentally valuable?

What are 10 things that you think are finally valuable?

What are 10 things that you think are intrinsically valuable?

What are 10 things that you think are extrinsically valuable?

Tip #1: Even if you do not think, for example, that there is anything with intrinsic value, it will still be useful to list 10 things you think could have intrinsic value. Alternatively, you could list additional examples for the opposite category.

Tip #2: It can help to think of specific things in your life that are important, such as something you spend a significant amount of time doing, or worrying about.

Tip #3: It can also help to reference your list of 10 core values from last week's newsletter, since many of these values could be considered intrinsically or finally valuable.

By the way, if you have not already received the free Value Builder Template, which contains last week's assignment, and a list of 100 human values, you can access it for free by following these 2 steps.

1) Sign up for the Kortex writing app (it's free): Sign Up Here

2) Follow this link to the template, and click "duplicate": Value Builder Template

I hope you found this this newsletter helpful.

Thank you for reading.

-Paul

Paul - this is a huge amount of bang for the buk in terms of knowledge and how to go about thinking through not only what is valuable in our lives but different ways to live them out as well :)

Well done Paul!